“Being hyphaenated is an attempt to fight against the single point perspective in general, and the human perspective in a broad sense. We now understand that the whole planet is connected, and the behavior of one thing changes–sometimes dramatically–the behavior of another.”

Cesar & Lois is an art collective that probes humanity’s relationship to the planet by interweaving technological, biological and social systems. Their practice layers living networks, like mycorrhiza, over human technologies in order to challenge anthropocentric thinking and move the future of technology towards embodied planetary (and plant) intelligence. Cesar & Lois’s artworks often propose artificial intelligences based on those living networks, imagining machines that learn from Earth’s ecosystems. Formed in 2017 by Lucy HG Solomon (California, US) and Cesar Baio (São Paulo, Brazil), the collective has received numerous international awards for innovations in media art, BioArt, and the usage of AI.

Lucy HG Solomon: One of the things that comes up for us, and it came up in your article [refers to “A Brief on Complex Systems,” by David Familian], too, is this challenge of understanding timescales from the view of the planet. What processes take place over the course of millennia? We’re thinking about similar impediments to human sensing and engagement with real-time information that’s happening all around us through our lack of perception of wider scales of activity, both the molecular and the microscopic, and then planetary scales, while considering the independent systems and timescales of plants and fungi. We subconsciously consider these systems–of course, we’re always breathing CO2, we’re part of this breathing planet, but it would seem that intellectually we would have grown the capacity to feel the world in ways that would have maybe kept our own rampant development in check and our consciousness of the living world more in the forefront of our decision-making and our machines’ decision-making.

David Familian: Right, we tend to look at things through this one-point perspective. People still don’t see through the periphery of their vision.

Lucy HG Solomon: Cesar, I’m reminded of the first time that we met, and one of the things that made us interested in working together was your hostility towards one-point perspective. It was when we met in Plymouth, and you were talking about the tyranny of perspective, and I think that was at the core of some of our initial thinking, and widening that perspective to plants, to nonhuman perspectives. And then we looked at a lot of Indigenous-originating theories like multinaturalism and perspectivism, documented and coined by Déborah Danowski and Viveiros de Castro, who write of a perspective that is more community-based, of thinking along with and thinking through, in opposition to singular points of view.

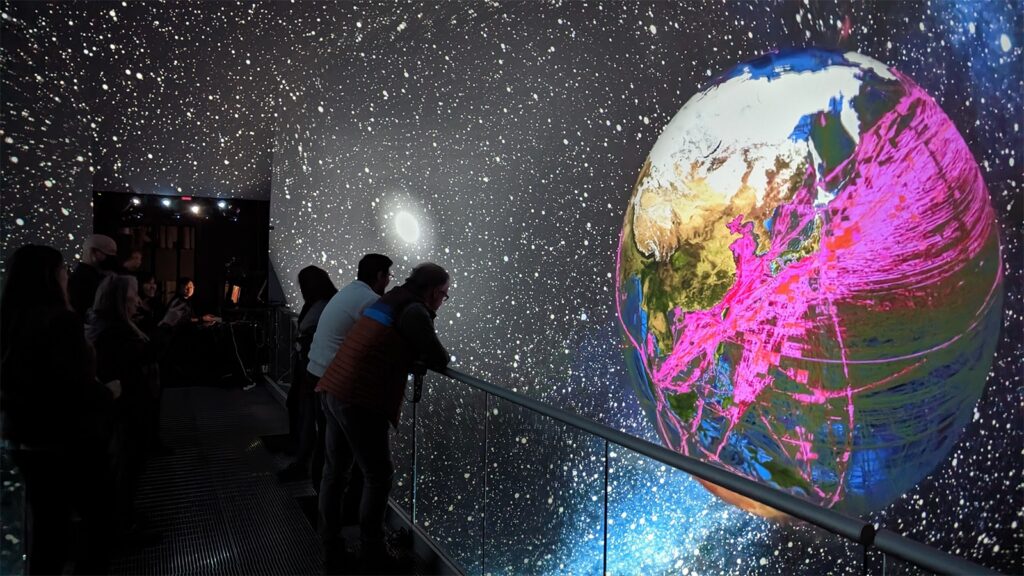

Cesar Baio: Yeah, I think the title of this work, Being hyphaenated (Ser hifanizado) is an attempt to fight against this perspective in both ways: the single point perspective in general, and the human perspective in a broad sense. We can now understand that the whole planet is connected, and the behavior of one thing changes–sometimes dramatically–the behavior of other living things in other parts of the world.

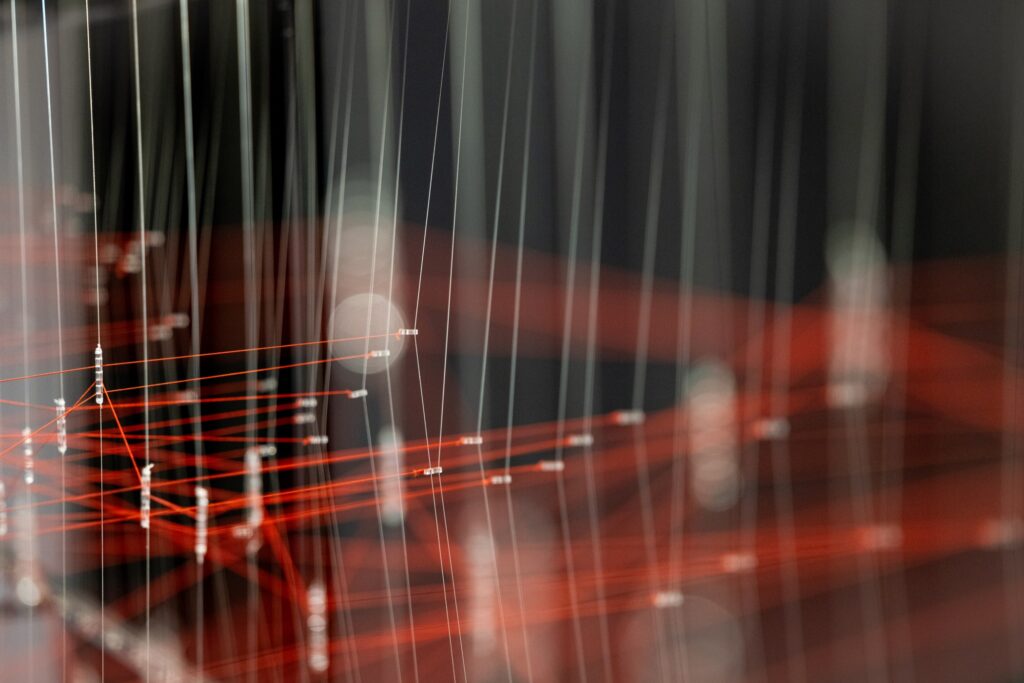

We don’t sense how complex this system is. We know rationally that the ecosystem is composed of many living beings that interact in ways that we cannot predict and that are nonlinear. When we think of a living being as connected to and dependent on its interactions with its surroundings, we understand how important it is for people to translate these relational interactions into an aesthetic experience.

Lucy HG Solomon: In this work, we invite people to imagine how we are part of this broad intelligence system. If we can make the leap to having more inputs into the digital and machine systems that we create so that they take into account not just human concerns but this web of interactions, that would be transformational for AI.

“In this work, we invite people to imagine how we are part of this broad intelligence system. If our machine systems could take into account this web of interactions, they’d be transformational.”

Cesar Baio: I think you’re right when you point out that our work is really based on interactions. We are talking about these complex interactions. And, of course, as artists, we can only track a few of them. However, by tracking these few interactions, because there are many interactions between these organisms, we can also talk about what emerges from these interactions. You could think, for example, that living beings are fighting at any moment. When our bodies get sick, they’re fighting for permanence. When we get sick, our bodies are seeking to self-organize in a way that allows the body to survive.

When we think about climate change, there is an inevitable crossing of these two different forms of intelligence—human intelligence and ecosystemic intelligence–and by that, I mean intelligence that emerges from the forest, from the ecosystem, from the whole planet, which makes life possible. How these interact is a key point for us not only to understand better what life is but also to stay alive as humans and as a society.

Lucy HG Solomon: Right now, there are so many existential dilemmas that humanity moves forward with, like the continuation of new nuclear testing, which is likely, and all of these human decisions that make no sense. There’s no check on our destruction of a planet, despite the patterns that have already shown us that we should go in another direction. If we’re gonna trust AI to do so many other things, maybe we could trust it to keep some of our worst impulses in check–not a human-based AI, but an ecosystemic AI.

David Familian: Or it’ll do it for us. But I think one of the things I’m hearing from both of you, too, is that we have to stop simplifying the complex. Our minds want to simplify and simplify further, and that’s what the right-wing does and what the left-wing does. Everyone wants to simplify and essentialize. And the idea is we have to take this wider view and accept that there’s nothing to simplify anymore. There is no simplicity. That is an illusion–an aesthetic illusion, really. I think it’s an illusion that died with Einstein’s e=mc2. Since his discovery, we haven’t been able to simplify the way we had been.

For 300 years, simplification was a successful method for understanding our world. But we’re not doing anything with that understanding. That’s one of the things introduced in the cybernetics conference: the question of whether scientists and the world will ever accept the complexity of these systems. There exists a constant and simultaneous pessimism and hope.

Lucy HG Solomon: What’s funny is that, even in accepting complexity, we’re also looking at some of the simplest interactions. In our own bodies, for example, multiple organisms in our gut compete for our decision-making.

David Familian: That’s what your work has been about and why I wanted you involved. You make it simple so people see the complexity. For the general public, we want to simplify the problem without getting rid of the complexity. That’s what, I’m hoping, a lot of the works will do, that they remain legible and engage a few discrete systems while the exhibition bombards visitors with the whole of global complexity. Though my initial instruction to the artists was to allow visitors to feel complexity viscerally, that can only happen if each work is not too complex.

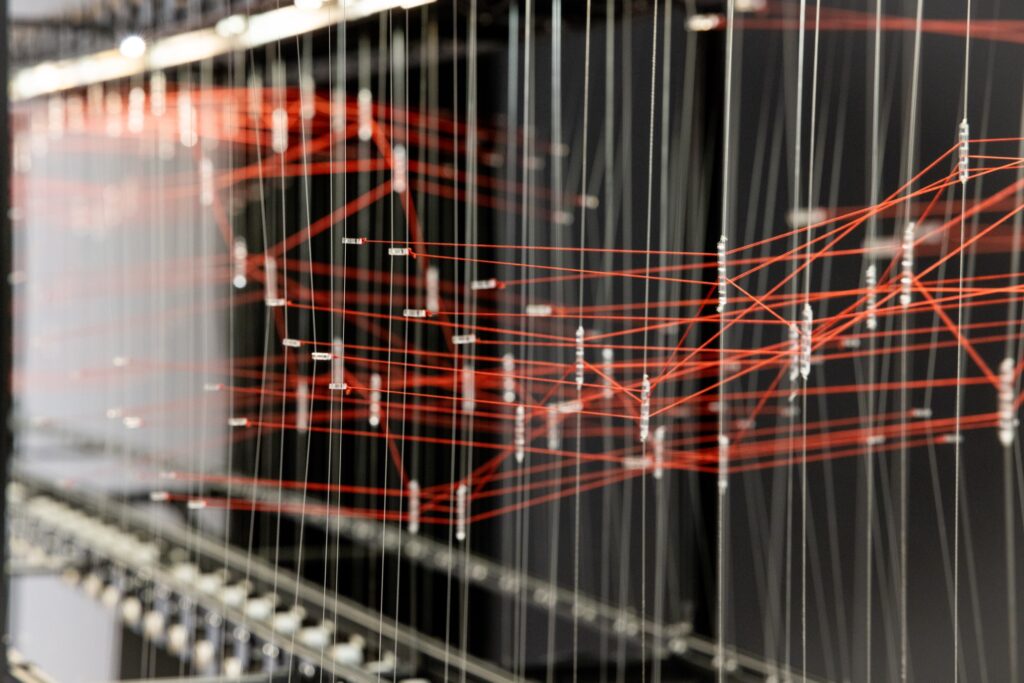

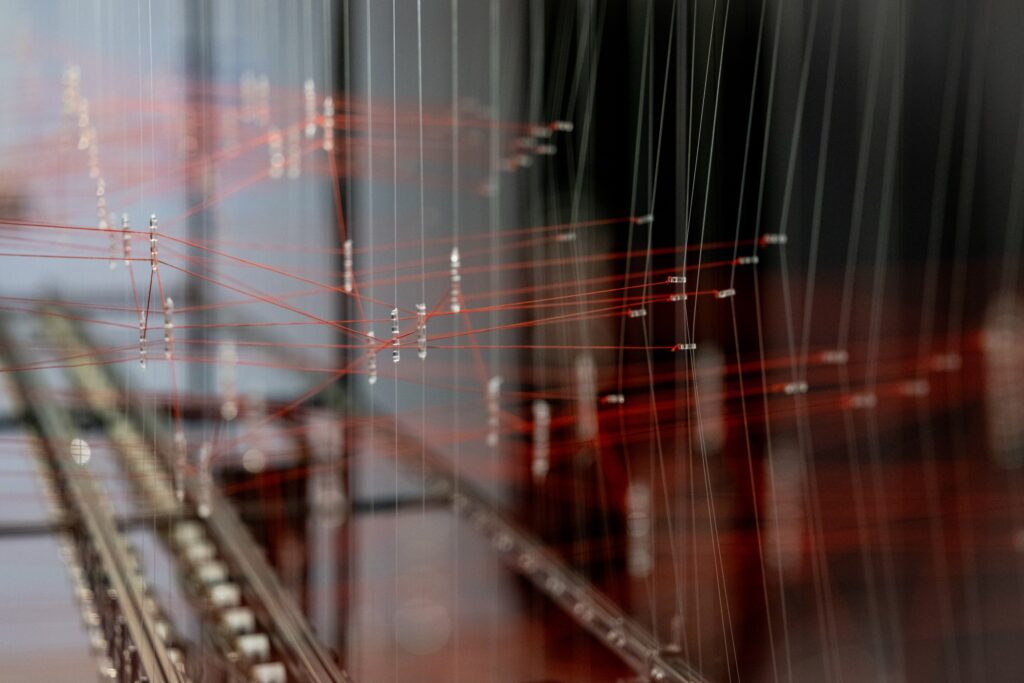

Cesar Baio: I think this is an interesting aspect of our work. As a viewer, you can relate to our work on different levels. Without approaching the work too closely, you can see the lights but not the organisms, perhaps, but you can feel that something is happening. The interaction between the lights is implicit. When you get closer to the work, you see the wiring and the living organisms, and you see that they are connected within a system. So, some responses are being collected and presented, and you understand that some sort of feedback loop is occurring. And then you see the interface, which provides more information. You can go one or two steps deeper into how these complex interactions are taking place and what is happening within the artwork.

So, as a viewer, you can enter as far as you’d like, and at each point, you can construct a different understanding of the work. If you spend time there, you will see the system’s patterns changing, and you can read on the interface how the CO2 you are breathing is changing the behavior and signaling of the organisms. This is something we want people to experience in our work.

“As a viewer you can construct a different understanding of the work. If you spend time with it, you’ll see the system’s patterns changing, and the interface shows you how the CO2 you are breathing is changing the behavior and signaling of the organisms.”

Lucy HG Solomon: Small shifts can significantly change our perspectives.

David Familian: There are different systems of complexity that exist in the city and in nature, but I think we just have to learn to see it everywhere. When you talk about the patterns changing, do you see emergence happening all the time, or do patterns build up? This is where the temporal thing comes in. Patterns generate the energy for emergence, which may lead to self-organization. The other thing that seems apparent in the work is that regulatory homeostasis is an illusion. Because once you have emergence and self-organization, it may seem to be an equilibrium, but the system has changed.

Lucy HG Solomon: I think of this work as a question. We’re wondering what patterns will emerge. Having these systems in observation in this setup for this amount of time is as close to a laboratory experiment as we can construct, and it may reveal whether patterns emerge from chaos.

David Familian: After the piece has exhibited in Future Tense, do you imagine that the work would continue to run as an ongoing experiment?

Cesar Baio: Actually, we want that. We are engaging more scientists and technicians to help us observe and extract more scientific data from what we are building and what we are doing as artists and to frame our project in scientific terms. Regarding emergence, the work evolves. It does not reproduce what we understand as nature; rather, it responds to a concept that has become very important to the environmental movement in the last two decades. That is the concept that everything is integrated and that we cannot separate from nature.

Lucy HG Solomon: Back to the web of life.

Cesar Baio: That’s why we directed AI to these living beings, which are working and communicating with each other, because we are also complex, and our technology is complex, and everything we project from our minds gets into this whole web of life.

We are not thinking about going back to some imagined time before technology. We cannot forget our culture; we have to rethink and rebuild. Other experiences of nature and technology, such as those that we try to create as artists, can give some insights into how different intelligences can integrate.

David Familian: So, how is your project using generative AI and General AI for pattern recognition?

Cesar Baio: General AI ideally behaves and acts like a human. In our work, we try to imagine a general AI that could behave like a planet or a forest. We wanted to shift away from a human-centric perspective and think of AI as capable of following not only human criteria and models.

Lucy HG Solomon: That’s true of Degenerative Cultures, which uses Physarum polycephalum as the model for an AI. In developing that project, we were thinking about nonhuman information and complexity and some of the limitations of humans that we’ve already talked about: scale and the lack of a human capacity for sensing that leads to a lack of empathy for a planet, for other living beings.

David Familian: That’s what Jim Crutchfield proposes in his work. People get really freaked out when they hear it because they think he’s suggesting that nature operates along computational processes, but he’s not. Natural intelligence could form a language or chemical or biological systems.

One of the things I thought was interesting about your piece is that it attracts scientists in a way that makes one wonder whether its appeal is the concept of the experiment you set up, or its artistic qualities which entice them to enter this world you’ve created. Scientists don’t create worlds.

I’ve had colleagues at Irvine come into some shows and say, “Oh, that’s not art; that’s a science experiment.” And they’re partially correct, but what I like about your piece is that it’s a living system. A lot of BioArtists don’t work with real living systems, they work with artifacts of living systems. Being hyphaenated will continue to live. I think it’s interesting anthropologically, the fact that scientists are so compelled by your work.

Lucy HG Solomon: I think our engagement with the Treseder Lab was mutually invigorating. A lot of the scientists aren’t used to non-scientists tackling these questions from a totally different angle. Multidisciplinary collaboration opens a rare opportunity for discussion that scientists, even engaged environmentalists, don’t have in their labs. We’re so invested in scientific information, as artists, because it’s a key component of building the artwork, and it allows us to ask deeper and deeper questions that circle back to the relation of their research to other fields, to the planet. It may be inflating our work to say this, but I do think we offer an opportunity for people to engage with scientists’ critical interests in ways that scientists don’t normally get.

“Many scientists are not used to non-scientists tackling these questions from a totally different angle. Multidisciplinary collaboration opens a rare opportunity for discussion that scientists don’t have in their labs.”

David Familian: I was talking to a woman recently who received her PhD from ZKM, and we were talking about how even complexity scientists are focused within a discipline. Even at the Santa Fe Institute, transdisciplinary practice does not necessarily happen the study of complex systems because it’s hard to get funding—because it’s too unfocused.

I pick artists that know their field. So the response you’re receiving from the scientists is not uncommon for a Black Box project. I really let the artists navigate our system on their own and see which scientists resonate, naturally allowing things to happen, and it seems to work. What’s essential is that both the artists and the scientists are collaborative.

Cesar Baio: When you do this kind of art and deal with these kinds of complex questions and complex systems, the most challenging part is how to navigate from highly specialized and often hard-to-understand scientific concepts, to experiments, to scientific papers, to artistic concepts, to the artifact–the materiality of the work. It can be something that is not didactic, like some educational tool, but that is meaningful and creates momentum when a person encounters the artwork.

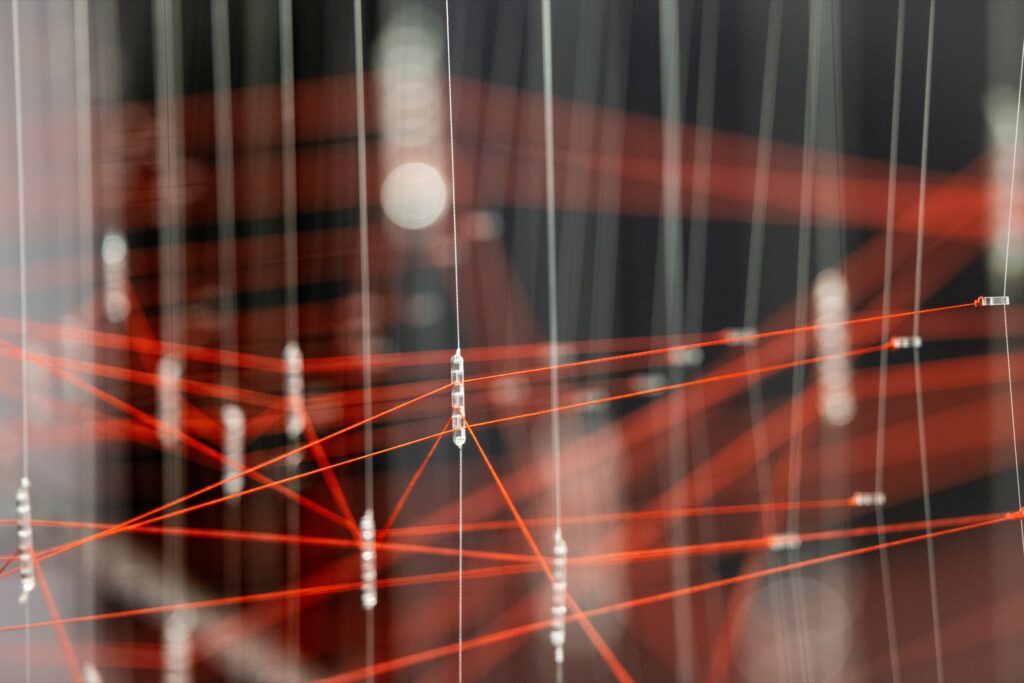

Lucy HG Solomon: In this project, we’ve moved towards sculptural elements such that the work becomes a conceptual mirror, so that there is both this simple organism, the shape that you’re looking at that’s clearly some kind of nonhuman entity, and then there are all of these sub-components that are in that larger entity. I think these questions about scale, simplicity, and complexity intuitively start to build within this weird creature that is the project.

David Familian: I was imagining what happens if this gets bigger, and becomes the size of a room. I think you’re right that this will become a template, a foundation for something that you’ll be working on for the next ten years or so.

Cesar Baio: Yeah, I think this is something to point out–the process of the residency. You gave us the freedom to work in this way. We spent this whole year maturing and thinking about possibilities, and expanding and contracting and navigating between complexity and simplicity, with these different scales of information, and through science and aesthetics. The residency was a period of time when we were building concepts, building materialities, and building knowledge through the artwork and through the process.

It’s not something that you say what you are gonna make, and then you build it.

David Familian: I appreciate that. I didn’t know exactly what you were going to do. And, you know, I knew you were going to do something. But, you know, I get anxious…

Lucy HG Solomon: One last thing to say is that I know you quoted Barry Richmond, and this idea is that, as humans, we must learn to see both the forests and the trees simultaneously. In this artwork, we’re really trying to think about experiencing the almost microscopic or chemical exchanges and an entire ecosystem, and through that, to allow viewers to get a sense of their relationship to this one component as a small entity and as part of an ecosystem with the goal of seeing the forest and the trees simultaneously.

David Familian: In reality, it’s hard to see the forest and the trees. It’s not just conceptually hard. If you’re in the forest, you’re surrounded by these trees, you’re embedded in the midst of the environment, whereas the scale of your piece allows for viewers to create the distance necessary to see at both scales.

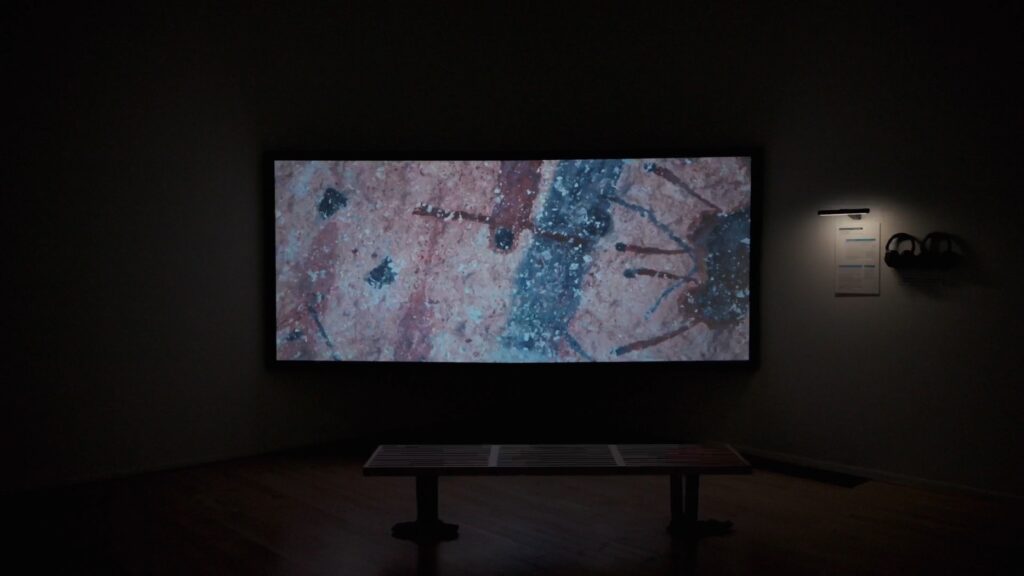

→ Cesar & Lois, Being hyphaenated (Ser hifanizado), 2024