“At the most basic level, I’m trying to evoke the environmental influences on gene expression, how genetics is not operating in a vacuum but is affected by external stimuli.”

Laura Splan is a New York City-based artist exploring intersections of culture, science and technology. Often working collaboratively and between disciplines, Splan’s practice reframes artifacts of the posthuman landscape. With an approach grounded in the “tactical tactile,” Splan’s

work cultivates intuitive and embodied comprehension of the interconnectedness of cultural and biological systems. Her research interrogates the “GUI/gooey” or liminal spaces that mediate our relationship to nature and to our bodies. Splan has exhibitied her work internationally and is held in collections including the Thoma Art Foundation. Commissions include projects for the CDC Foundation, Vanderbilt Planetarium, and the Bruges Triennial.

David Familian: My point of view now is the feedback is the engine: everything else evolves from it. There are two types of feedback: the general feedback around the environment, the outside and inside; and then there’s regulatory feedback, which is like when one gland secretes a certain hormone as its sole function.

Laura Splan: I also kind of kept bucketing everything under feedback.

David Familian: That’s the framing. You can’t understand any of the other stuff if you don’t understand how the system you’re looking at uses feedback.

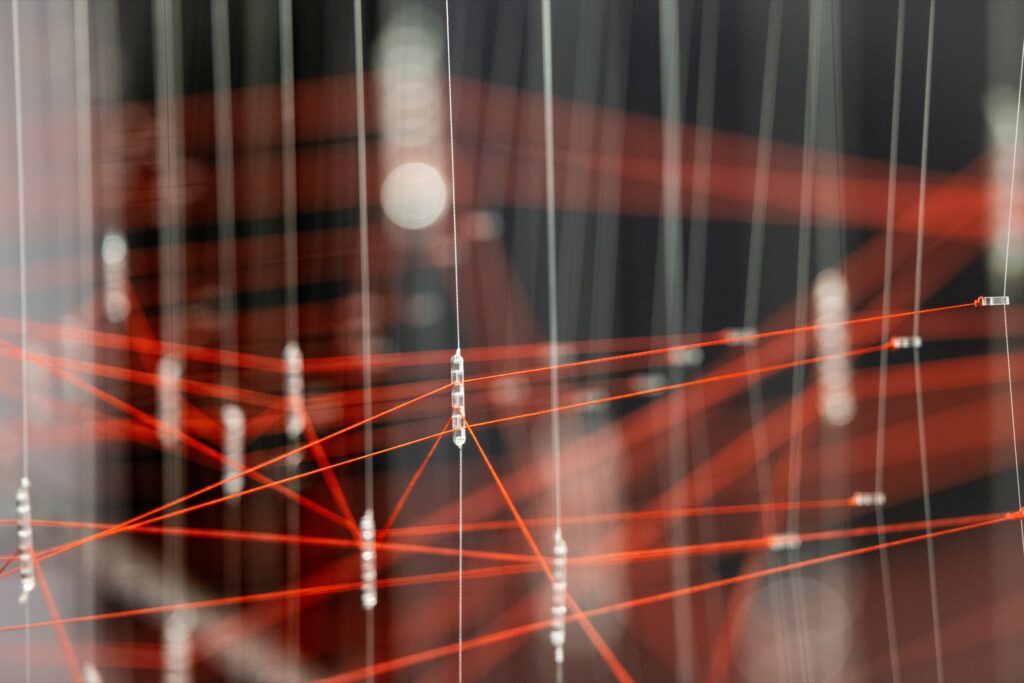

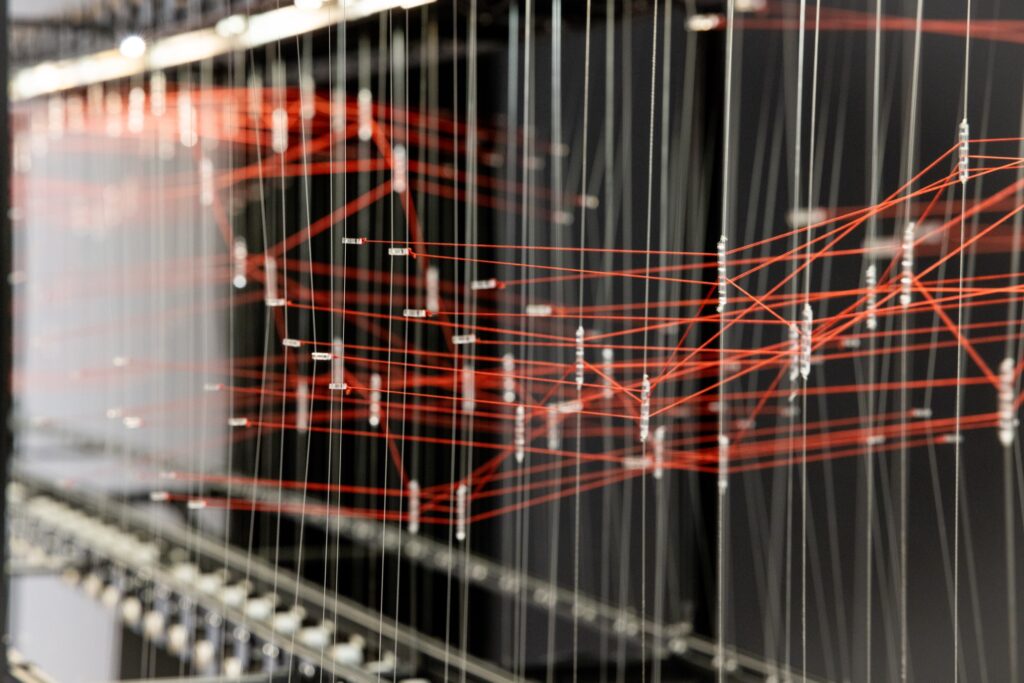

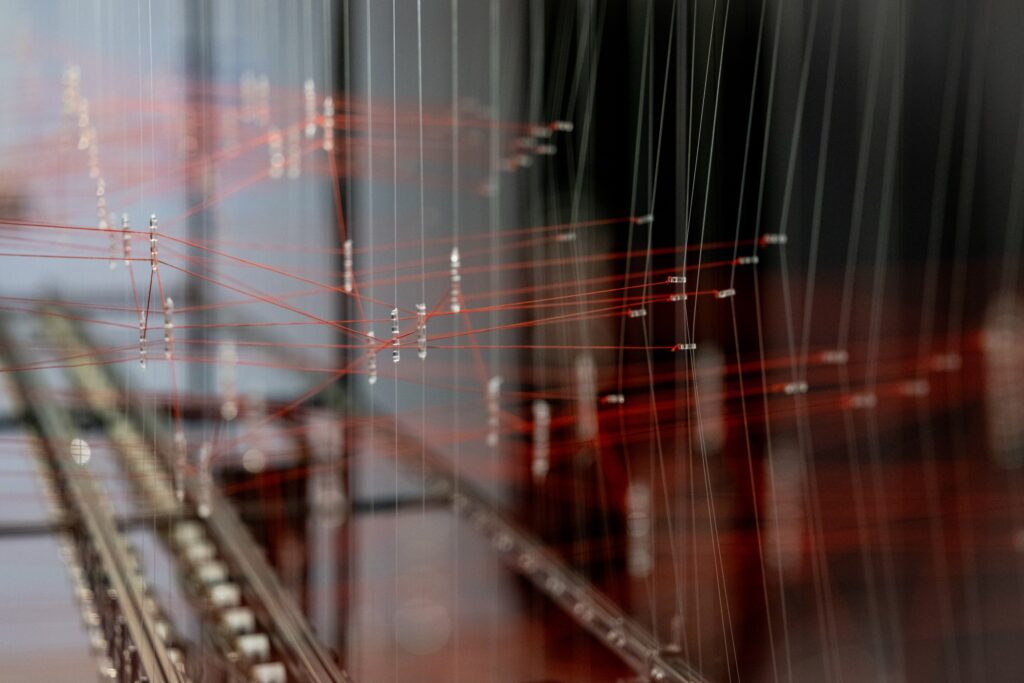

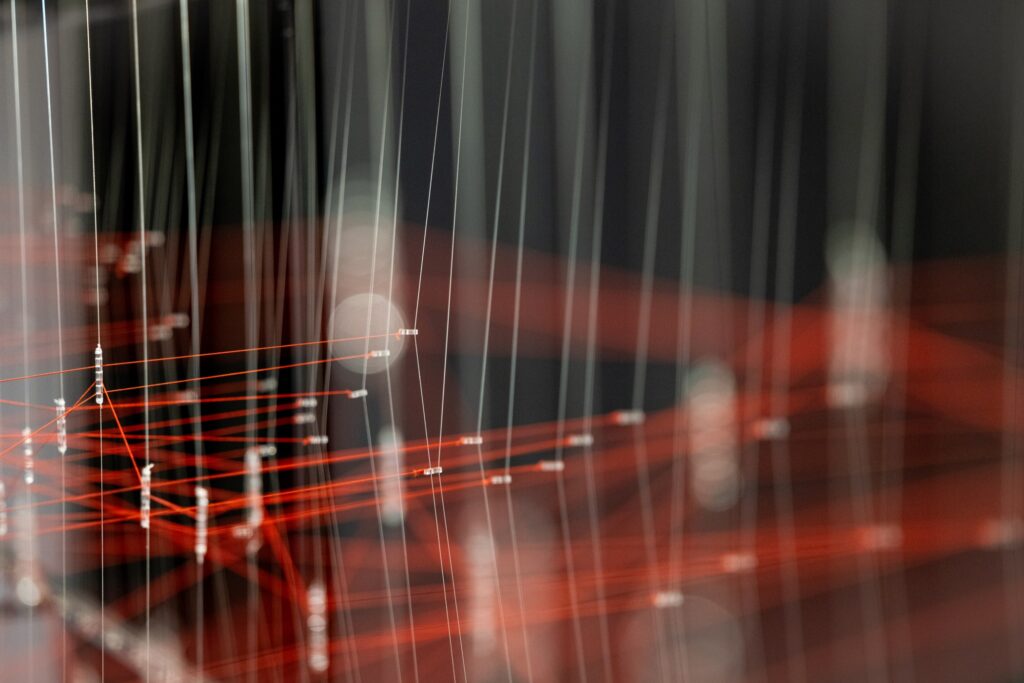

Laura Splan: On a high level, the piece, Baroque Bodies Sway, is intended to be this sensory encounter where people are hearing, they’re seeing, and they’re also moving and interacting and seeing other people move and interact. And all of the imagery and sound and research behind it, as well as the technology used to create it explores these entanglements between molecular bodies that are within our bodies and the built environment. And so it’s trying to locate these different nodes–I’ll use a term from your essay–to reveal the circuits among them. It’s trying to do that visually, and also through visitors’ agency.

Another couple of things around the elements of the installation: so there’s the interactive installation, where people moving through the space become some sort of external stimuli for the system of the installation itself. And they’re also actuating sound. Just on a really basic technical level, my work exhibits feedback loops and also processes internal and external stimuli. It’s people moving through a space and actuating a 3D model on the projection and being compelled to move more closely to that projection in order to inspect the landscapes that are reflected in the histone proteins of the nucleosome model—landscapes which are AI generated. The sounds were created in my collaboration with Adam Lamson. He was able to generate sound files off of his chromatin simulations, and then I took those and applied MIDI instruments to them. So there are multiple nodes and circuits happening in the artwork, which we can come back to.

There’s also the scaffold of the science of epigenetics that the whole piece is relying on and is inspired by. It’s a wonderful way to talk about every single one of these things that you’ve pointed out: uncertainty, feedback loops, and the emergence of new patterns and behaviors.

The thing that interests me about it and the thing that I’m trying to evoke, at the most basic level, is environmental influences on gene expression, how genetics is not operating in a vacuum—it can’t be reduced to genes—but it is affected by external stimuli or environmental influences. All of this having implications for disease or sensitivity to stimuli like scent or impacting phenotype.

“All of the imagery, the sound, as well as the technology used to create the work explore the entanglements between molecular structures that are within our bodies and the built environment. People moving through the space become external stimuli for the system of the installation itself.”

David Familian: What makes yours even more complex, and it’s going to be a challenge to display, is that the body has its own systems, of which DNA is the primary driver. But then you’re looking deeper into the complex system of DNA, which is also vulnerable to the outside world. So it’s a deeper kind of mutation.

Laura Splan: I think what you’re talking about is a mutation in the DNA sequence, versus epigenetics, which looks at how the same underlying DNA sequence is being expressed differently based on environmental influences. This is where complexity and uncertainty are introduced. You’re dealing with infinite possibilities that are unique to space and time.

David Familian: How does epigenetics translate environmental influences into mutations or diseases? What’s the pathway?

Laura Splan: It has to do with which genes get silenced and which are available to be expressed. The nucleosome model that I’m using in the exhibition is eight histone proteins that have DNA wrapped around them. That is a nucleosome. A nucleosome is a component of chromatin. Chromatin is the structural foundation of how DNA is packed into your chromosomes. And it could be packed in different ways. So that’s where Adam’s biophysical simulations of chromatin configuration are important in thinking about how DNA packs into a chromosome, and how that makes different parts of the sequence available or unavailable to be expressed, and that can be influenced by something like pesticides exposure.

One of the compelling research articles I found early on that really turned me on creatively to epigenetics was this study, where mice were exposed to a cherry blossom scent while they were being electrocuted, and then they took the electrocution away, and they would introduce the scent, and the mice would still have a trauma response to the scent, even though they weren’t being electrocuted. This response was then observed in not one, but two generations of their offspring who had not been raised by their parents and had never been electrocuted. It was a heritable trait that was not a change in the genetic sequence. It was a change in how certain genes were expressed.

David Familian: Right, so even though the sequence is the same, the way it expresses can be altered.

Laura Splan: Yes, and it can be altered over generations and over time.

David Familian: So, is the nature of these alterations to gene expression comparable to altering the speed at which a musical score is played, or missing a note? It’s almost like a DNA is a piece of music that can be played in different ways. And these all the things you’re talking about can affect how it’s played.

Laura Splan: That music analogy is really useful, and it’s why I love having sound in this piece as well. Every time somebody enters the space, they’re introducing another sound sequence. The soundscape is always going to be different, it’s never going to be the same, because people are always going to be entering at different intervals, and there will be a different number of people in the space at any given time. So the soundscape is one attempt to kind of materialize that variation.

David Familian: These kind of analogies will explain what gene expression actually means. Because it doesn’t immediately compute, when you hear of epigenetics. It’s too abstract.

Laura Splan: Participants can manipulate the cameras’ movement and point of view on the 3D model with their movement through space. So, the closer they get to the wall, the more the camera zooms in. The further they get from the wall, the more the camera moves out. But then there’s also this uncertainty, variation, maybe chaos even, presented by how many people are in the space, and if somebody is standing still they lose control. You have to be moving in order to be influencing or ‘swaying’ the visuals and sound.

David Familian: If there’s a group of people that spend enough time with it, would the chaos start to order itself in some way? Or will the number of people create a chaos?

Laura Splan: Everybody who’s moving has equal sway. So if people are moving divergently, there’s not a lot happening. But if they move together, the model is more responsive. If there’s just one person in there moving, and then a bunch of still people, that person has 100% sway. But there’s also this added uncertainty that comes from the emergence of patterns of behavior that has to do with social interactions and people being influenced by what other people are doing or not doing. And that’s the uncertainty part of it that has to do with human personalities and social behavior. So there’s the programmed side of the piece, and then there’s the unprogrammable side of the piece, which is human behavior, and the kind of soup of influence that happens depending on who’s in the space at any given time.

“There’s the programmed side of the piece, and then there’s the unprogrammable side of the piece: human behavior and the soup of influence depending on who’s in the space at any given time.”

David Familian: If someone moves exactly the same way, will it do the same thing?

Laura Splan: Yes, theoretically. But it depends on the movement. If adopting a kind of wild gesticular movement, that could manifest itself a little differently in the visuals. This kind of tracking I’m using is called ‘blob tracking.’ So if somebody is moving like a very similar blob to the camera, then yes, the camera would behave the same. Though we haven’t tested that particular issue yet.

The thing I’ve been playing with, and in some ways struggling with, is how to negotiate the reward system of ‘something’s happening,’ and also that problem of the ‘waving the hands.’ I don’t want it to be a one-to-one tool, or mirror interface. And in that not wanting to be a one-to-one mirror, there’s kind of a liveness to it that has a certain sense of its own agency. So I’m negotiating that in the programming side of it.

David Familian: We have been influenced by the design interfaces of our computers that are predictable all the time, so in projects that subvert a one to one interaction relationship, the struggle is to try to not make people think it’s broken, but that it’s structured. And that’s what I’ve been asking artists for years to think about.

Laura Splan: I think that the way that the piece is positioned in the gallery is going to benefit it. The fact that you’re not going into an enclosed space, where you’re only left to wave your arms, in some ways like is actually a benefit. I also like the idea that there’s incidental interaction where people are just moving through the installation space. But there’s also the intentional exploration that you described, which is inevitably going to be somebody waving their arms. I really don’t want it to seem ‘broken,’ so I am favoring the mirror over the personality of the nucleosome. But that’s definitely something I’m trying to master.

And there’s still this other layer of discovery and inspection of the landscapes, and there’s also the other layer of the sound, that the sound is always changing. So I hope that there is enough there for people to kind of be curious about.

David Familian: I think it was Caroline Jones that asked about the landscape in the reflections. There are two parts. One is the Baroque. People don’t understand the concept of the Baroque. Deleuze wrote about its folds, that it was about folds, which is what your piece is about. The second thing is the Age of Wonderment decoration or alteration, and this work is also in that tradition. The Baroque has kind of a bad rep, and we don’t think about fugues and sculptures that had cloth folding in it, that is not overly decorative, it’s expressive and very temporal.

Laura Splan: Yeah, and I was also thinking about it in terms of a baroque system, like a baroque bureaucratic system where that’s completely impenetrable. It has a bad connotation in terms of being unnecessarily complex.

David Familian: Right. But to me, no one’s done anything better than a fugue. Anyone could take that original theme and come up with a total different set of counterpoints. There’s no rule. I don’t know if anybody’s ever done this, where they ask ten composers to take the same theme and create a piece of music. That would be really interesting, because I think that’s what’s amazing about that process.

Laura Splan: The other point that I was thinking about was from a procedural art perspective. Historically, I have developed elaborate rule systems to make my work. And I was really embracing that with the AI landscape generation by using disruptive prompts within Midjourney in ways that it wasn’t really intended to be used, and that being part of this absurd process of generating a landscape that looks like a really familiar landscape and didn’t need to be generated with AI. So the absurdity of the baroque is another part. I appreciate your thoughts on that. And then there was a whole other element about baroque peacock pearls. That was part of my collaboration with Adam. It continues to be an interesting reference point for me.

David Familian: And that book, The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque (1988) by Deleuze, is almost impenetrable. I tried to teach it once, and totally failed at it, but I still take away the main points from the book that one can see in your work. And also the Baroque is when you have the quantification of the rate of change in a system. Calculus is figured out. Deleuze talks about liveness, too. So it’s all there.

Laura Splan: The other thing was, you know, I talked about participatory and accidental or bystander movement or stillness. I talked about the mirror quality as a tangible feedback, but also with elements of uncertainty where I’m negotiating the viewer’s sense of agency and control. Those are the things that I’m trying to kind of destabilize in an artful way.

David Familian: Can you control how far back it reads?

Laura Splan: Yes.

David Familian: That’s sort of the thing you’re figuring out, because you’ll have someone interacting.

Laura Splan: Yeah, my plan is to use the entire square or rectangle in front of that wall all the way to the door. I have four RealSense cameras.

David Familian: Oh, that’s great. That answers my question. It could be interesting if they’re there alone, and they go, “Oh, I got control of it.” And then people start walking around and they start losing control. So there’s a lot of narratives that I could see being expressed.

Laura Splan: Yeah, and that’s where the kind of sway really becomes materialized and also politicized. Who’s in the space, who’s taking up space in the space.

I was also thinking of the AI image generation as a feedback loop of sorts, where the Midjourney model is trained on existing landscape images that have existing text descriptions. And that’s one of the things that fascinates me about this regurgitation factor of AI-generated imagery. And how, with the landscapes, certain language is used to describe them, like ‘panoramic landscape photography,’ without including the photographers’ names or anything like that in the prompts, that it continues to generate these idyllic-looking landscapes that seem a little uncanny to me. They have a little bit of a haunting quality, but they’re also kind of idyllic, with pink clouds, blue skies, and green hills.

“People navigating and negotiating control over the installation is where the ‘sway’ becomes materialized and politicized. Who’s in the space, who’s taking up space in the space?”

David Familian: It’s like surreal, or science fiction landscapes.

Laura Splan: Yeah. I’ve really enjoyed working with this existing feedback loop of AI image generation, but also trying to disrupt it. And there’s also an uncertainty in that process, where there’s like a slot machine quality to it, where you’re just like, “what is it gonna spit out this time?” We are also going to experiment with switching out landscapes on the visuals with interaction.

Correlating nodes and circuits with the nucleosome, the histone proteins are the nodes. That’s where the DNA methylation happens. And then the gene expressions form the loops. And then exposure to environmental influences like scent or pesticides form the inputs, and disease, sensitivity, and phenotype form the outputs.

David Familian: Is the histone affected by this? Is that where things like smell and trauma get associated is in the histones?

Laura Splan: The histones play a role in DNA methylation, where genes are either expressed or silenced, or available or unavailable, and affect how chromatin is configured. The histones within the nucleosome are the ‘beads on a string’ of chromatin, and they’re packed into a chromosome, and how they pack into the chromosome is influenced by these molecular processes happening at the histone level. And that’s affecting the expression of genes, based on the way they pack into the chromosome.

David Familian: So, would it be correct to say that the histones are genetically inherited?

Laura Splan: The histones are directly related to what’s called genetic bookmarking.

David Familian: So when you inherit a trauma, that’s where the memory is held, in the histones?

Laura Splan: I’m not sure if I would put it like that. I also have been referring to Ellen Levy’s book, this Darcy Wentworth book that she mentioned in the Symposium meetings. There’s a really wonderful essay in there by Evelyn Fox Keller that gets right down into the science of epigenetics. It has some really wonderful explanations of epigenetics in relation to these questions that you’re asking me. It does a really wonderful job of tracing the history of the relationship between the convergence and divergence of physical sciences or physics and genetics. “In both cases, the assumption of a linear causal change promised explanatory reductionism, with the hope that an explanation of macro phenomena could ultimately be reduced to an understanding of the properties and behavior of the lowest level entities or atoms–in the case of physics–and genes–in the case of biology.” I found this chapter in particular to be really helpful for thinking about your questions. I also pulled out a couple of other quotes: “Complex systems have many interacting, active components, and the interactions between components have non-trivial or nonlinear interactions.” These are things that were just resonating with me about epigenetics. Nonlinear in terms of generations and unpredictable variables of environment and experience.

As an artist, my goal is to create some sort of sensory experience that is felt viscerally in order to be memorable and to resonate with the viewer for days, months, or years after they leave the gallery, and so the interaction to me is really intriguing. And as you’ve mentioned, this is a piece that is using tactics that I haven’t done before, and they’re really exciting to me. I’ve always thought of interaction or engagement with artwork as a rehearsal for behavior or thought or understanding that you can take beyond the artwork. I really love thinking about the human aspect of this piece, and how unpredictable it is, and it’s kind of terrifying and also exciting at the same time. That will be a sort of performative demonstration of some of the complexity that I think this exhibition is trying to get at.

In terms of the work, I think that these signifiers of the macro and micro can invite embodied explorations of the natural world through these landscapes, and that will feel like they’re situated in this confusing liminal space that’s biological, technological, and then also autonomous and interconnected. I think there will be this realization, as you mentioned, David, that one person might be in the space by themselves, and then once somebody else enters, they realize that they’re sharing space, they’re sharing control, and they’re also sharing experience.

“The macro and micro can invite embodied explorations of the natural world through these landscapes. They’re situated in this confusing liminal space that’s biological, technological, but also autonomous and interconnected.”

David Familian: I really like that you’re using unpredictable interactivity. You’re giving up a certain amount of control, and I think that will always be a scary thing. Art should be scary. Technological artists tend to want to control too much and eliminate this fear, whereas traditional artists live in fear unless they come up with a style.

This is something I think I should mention in the essay, the artist’s giving up of control. When I asked media artists to try it ten or fiteen years ago, I would just get a blank look. They’d just go: “Why would I want to do that?” And to me that’s antithetical to what you’re saying about being scared. And I love that you admit that it’s scary, because it should be scary.

Laura Splan: Well, the other thing, too, is that I am very particular. I spent so much time making those animations that I showed you in my studio, where I was obsessing over, like, whether the light should be at 90 or 91. And this progression, this evolution, this translation, this iteration of this body of work has so many factors that are by design not controlled.

David Familian: That’s sort of a good analogy of a complex system, that if we want to experience complex systems or learn to solve problems using systems thinking, we have to give up a certain amount of control that we expect to have. Because it’s an interesting thing. I just watched the beautiful mine and there’s the scene where he, Nash, does his theory, and he says that Adam says that whatever the individual goes after will be good for the group, and Nash said, “No, what’s good for the individual and the group is good for both,” and then you sit there, and there’s no explanation of well, how does that happen? How does the individual in the group get negotiated? Of course it does gets negotiated in game theory, where you have diplomats talking to work out what’s good for the both. But I think we’re still figuring that out. How do you negotiate so that the individual benefits as well as the group? And whether it’s a social thing or in any system, how do we negotiate the individual elements with the whole? I think in the essay I said, “you have to see the trees and the forest at the same time.”

Laura Splan: I think that’s what I really love about the companion workshop to this body of work. I love developing the idea of this workshop with Hannah, because when I first came to her, I think I really only knew that her lab was exploring pesticides, and that was enough for me to be like, “Oh, this could definitely connect to my work.” But then, when I realized she was using blood and urine testing for that, which shouldn’t have been a surprise, I was intrigued further in thinking about the gooeyness of this expanded biotechnological apparatus that includes our bodies and bodily functions. But anyway, I really love the contrast that that lends to what is actually a pretty hygienic art experience.

David Familian: Right. And it also relates, I think, to Jim Crutchfield’s idea of information being part of the system. There’s a kind of information processing. And I think that urine testing is a form of information processing. And actually, it’s very controversial, since it seems like you’re making an analogy with computing. But I don’t think Crutchfield is doing that. He’s saying that information is its own language. It’s its own information processing. But it is processing information. However, you want to say it, it’s doing something and reacting to it. So in the purest form, it is information. It’s not [Claude] Shannon information, but it’s information. And this is a way of reflecting on that idea too.

Laura Splan: Yeah, and if we do food testing with dipsticks in the workshop and have immediate results, seeing how something that’s gooey and material can get quickly translated into data, into numerical data, and then also, with the urine testing, seeing how your body and its vulnerability can get located or reduced or translated into a data point.

David Familian: And also that urine testing is revealing the altering of the information. It’s saying you have something going on here, that information gets in your body.

Laura Splan: Yeah, I mean, the testing that we’re talking about is only testing for exposure. It’s not actually able to detect DNA methylation.

David Familian: And the Sway is related to the Baroque fold in a weird way. The sway is doing some of the work of the fold, where in Theresa’s work, for example, which is static, and visitors have to do the swaying in their imagination.

Laura Splan: Yeah, I think it has a lot of nuance that can be referenced in different ways and embodied in different ways.

David Familian: It feels like an older word.

Laura Splan: Well, what I like about it is that it’s kind of gentle sounding. But it can also be this invisible force that can be powerful and influential, and maybe even undetectable.

David Familian: I mean, this is the butterfly effect. Like you’re saying, it could be both. It could be something with intention, or it could be something in the environment that makes you move.

Laura Splan: Yeah. And I really like that it lends itself to this interpretation or relationship to politics, with the idea of political sway, which is very much at play in agriculture. If you know anything about American agriculture, you know that it’s very entangled with politics. And so it’s kind of interesting to me, too, though it’s not something I’m speaking explicitly about. Sabine Seymour is doing a lot of work on that.

“People often reduce gene expression to being on or off. I’ve heard epigeneticist talk about it being more of a slider.”

David Familian: We’ve been programmed to think that everything’s in the DNA. And I think when people say that we inherit trauma, they think it’s in the DNA. I don’t think anybody understands what gene expression means.

Laura Splan: A couple of more things about that. People often reduce gene expression to being on or off, and I’ve heard some people researching epigenetics talk about it being more of a slider.

David Familian: So it’s like fuzzy logic. Which makes much more sense. Why would it just be on or off?

Laura Splan: And then also with the DNA methylation, making a gene available or unavailable doesn’t necessarily mean turning it on or off. Just because a gene is available doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s going to be expressed. So there’s a lot of nuance in the kind of mechanics and the physics of what’s happening, and its meaning.

David Familian: Well, it’s like with our synapses, and the question of whether there is a degree of how much electricity is in the signal. If we keep saying on and off we’re we’re reducing it to binary, which isn’t the way our bodies work. Our bodies are analog, not binary.

→ Laura Splan, Baroque Bodies (Sway), 2024